You recently published a long and detailed commentary on gun control and racism which I have read with interest and care. Your basic point seems to be that the usual response to mass killings, as reflected in President Obama’s first remarks about Charleston, is to call for stricter gun control laws which you believe will have the ultimate effect of increasing the racism of our criminal justice system while having no real impact on controlling gun violence, particularly mass gun violence. You assert that there are already too many arrests of minorities, too many racially-motivated defendant pleadings and too many incarcerations, all of which would simply increase if we institute more criminal laws to control gun violence in response to events like the slaughter at the Emanuel AME Church.

You also bring to the discussion some comments about research by scholars like Levin, Fagan and others concerning stop-and-frisk policing methods employed by the NYPD whose value in allegedly bringing down gun crimes has been evaluated in both positive and negative terms. Some of this research argues that stop-and-frisk was entirely based on racist assumptions about who might have been walking around with illegal guns, and that this strategy, useful or not, was yet another example of an extra-legal effort to combat gun violence that served only to engender racism between the police and the community whom they are sworn to protect.

You also bring to the discussion some comments about research by scholars like Levin, Fagan and others concerning stop-and-frisk policing methods employed by the NYPD whose value in allegedly bringing down gun crimes has been evaluated in both positive and negative terms. Some of this research argues that stop-and-frisk was entirely based on racist assumptions about who might have been walking around with illegal guns, and that this strategy, useful or not, was yet another example of an extra-legal effort to combat gun violence that served only to engender racism between the police and the community whom they are sworn to protect.

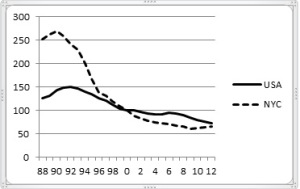

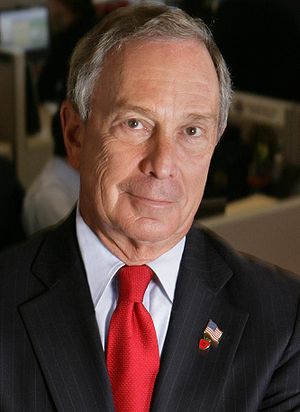

I’d like to respond to the second issue first. It’s true that New York City experienced an unprecedented drop in gun violence first under Rudy and then continuing with Mayor Mike. And much of this decline is tied to stop-and-frisk policing tactics which is obviously tied to racial profiling which is tied to racism, etc. But you have to be careful about perhaps pushing this argument too far. The decline in violent crime and gun crime in particular since the mid-1990s (although the decline largely flattened out after 2000) occurred in virtually every metropolitan center whether a change in policing and police tactics took place or not. In fact, an entire cottage industry has grown up around figuring out why America and other OECD countries appear to be less violent over the last twenty years. I am not sure that any of the multiple crime-decline theories explain the issue pari passu, but inconvenient or not, scholars have yet to settle on a single, determining factor when it comes to explaining criminal behavior with guns.

Now let’s move to your central argument, namely, that from the perspective of the inner-city community, more gun control means more criminal laws and, hence, more racism in the legal and penal systems that minority populations disproportionately endure. Nobody would or should argue that the penal process delivers equal justice to minorities and the poor. And with all due respect, we really didn’t need Dylann Roof to walk into Emanuel AME Church with a Glock 21 to remind us that racism is still alive and well. But where I think your argument falters is the assumption that because the President calls for more gun control, there will be more criminal laws that will result in more minorities getting arrested, going up before a judge on some trumped-up charge and then going off to jail.

What is really happening is that laws making it easier for anyone to gain access to a gun, or carrying a gun on their person, or bringing that gun into what was formerly a gun-free zone have increased exponentially, while laws that restrict gun access or restrict ‘gun rights’ are the exception, not the rule. One year after Sandy Hook, 70 new laws had been passed easing gun restrictions, while only 39 more restrictive measures had been signed into law, half of which concerned updating mental health records, a strategy with minimal impact on controlling the violent use of guns.

We need to defeat racism and we also need to defeat violence caused by guns. But each issue deserves to be challenged on its own terms.

Recent Comments