Since the health care industry now racks up revenues in excess of $1.6 trillion each year, there are plenty of online publications and other venues which are used to promote (i.e., advertise) the services and products driving this economic juggernaut. And one such venture, an online publication called MD Magazine, caught my eye because it published a survey of subscriber attitudes towards guns and counseling patients about guns – a hot-button topic in the medical profession ever since Florida passed a gag order prohibiting doctors to talk to patients about guns.

While the Florida law didn’t absolutely prohibit doctor-patient gun discussions, it just relegated such discussions to situations in which the physician had reason to believe that the health of the patient was at imminent risk. Of course since we are talking about behavior, it’s virtually impossible for a physician, or anyone else for that matter, to accurately predict imminent risk, which is precisely why doctors need the widest possible latitude in patient contacts, which is why doctor-patient relationships are circumscribed in every respect by the tightest degree of confidentiality, which is why the attempt to push the medical profession out of the discussion about guns is nothing more than pandering to the lowest, common intellectual denominator. But what the hell, if you can build an entire Presidential campaign around your ‘love’ of the 2nd Amendment, why not demonize doctors into the bargain?

While the Florida law didn’t absolutely prohibit doctor-patient gun discussions, it just relegated such discussions to situations in which the physician had reason to believe that the health of the patient was at imminent risk. Of course since we are talking about behavior, it’s virtually impossible for a physician, or anyone else for that matter, to accurately predict imminent risk, which is precisely why doctors need the widest possible latitude in patient contacts, which is why doctor-patient relationships are circumscribed in every respect by the tightest degree of confidentiality, which is why the attempt to push the medical profession out of the discussion about guns is nothing more than pandering to the lowest, common intellectual denominator. But what the hell, if you can build an entire Presidential campaign around your ‘love’ of the 2nd Amendment, why not demonize doctors into the bargain?

The good news about Docs-Glocks, however, is that it did result in the beginnings of a recognition on the part of physicians that they will only get back into the gun game if they bestir themselves and begin to argue for that role. Last April all the major medical associations issued a ‘Call To Acton,’ which not only endorsed the usual menu of gun-control options (background checks, assault-rifle ban, etc.,) but also made a commitment to be “part” of the solution to gun violence. Which means that, like it or not, physicians must continue to advocate for the widest possible freedom in talking to patients about guns.

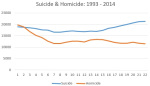

The problem with this more activist approach is that if physicians are going to engage in unfettered, candid discussions with patients about guns, they have to know how to frame the discussions in ways that are both understandable and meaningful to their patients. After all, the fact that the medical profession has decided that gun violence constitutes a serious medical issue does not, ipso facto, mean that doctors know how to explain the medical risks of gun ownership. Knowing that guns are the instrument used in 31,000 fatalities and 70,000 injuries each year is one thing; knowing how to use that information medically is something else.

This is the context in which the survey in MD Magazine needs to be understood because the results indicate that many doctors do not currently engage in gun counseling, nor do they consider gun ownership a proper issue about which they should be concerned. The survey, conducted online, was answered by 928 subscribers to the magazine. When asked if doctors should “play a role in curbing in gun violence,” 43% said ‘no,’ 40% said ‘yes.’ When asked if they had ever asked patients about gun ownership, 60% said ‘no,’ and 40% said ‘yes.’ It also turned out that 60% of the survey responders claimed to be gun owners which is a rather remarkable statistic for physicians, assuming that this magazine’s readership is at all representative of the medical profession as a whole.

If nothing else, this survey reflects the fact that, until now, medicine has not developed a clear and coherent medical response to gun violence at the level where it is needed most; namely, in discussions between care-givers and patients, which is ultimately where all medical responses to any kind of medical risk needs to start and end. The MD Magazine survey didn’t ask whether the survey respondents actually agreed that gun violence was a health issue. Maybe the magazine’s subscribers practice medicine on Mars.

Recent Comments