Between 1993 and 2012, the violent crime rate (homicide, robbery, forcible rape and aggravated assault) in the United States dropped by 48%. During the same period, the violent crime rate in New York City dropped by 71%. In 1993, violent crime in New York accounted for nearly 9% of all violent crimes reported in the United States, it’s now slightly above 3% of all U.S. violent crime, which is roughly the proportion of New York City’s population within the country as a whole.

The decrease in New York City crime became the signature accomplishment of Mayor Mike Bloomberg, who tied this effort to an aggressive street-level strategy known as ‘stop-and frisk,’ along with particular attention paid to ridding the city of illegal guns, the latter making him the national poster-boy for gun control efforts after the massacre at Sandy Hook. Bloomberg’s crime-fighting efforts were also augmented by the computerization of patrols and surveillance, known as Compstat, first introduced by his predecessor, Rudy Giuliani, whose Police Commissioner, Bill Bratton, is back running the NYPD again.

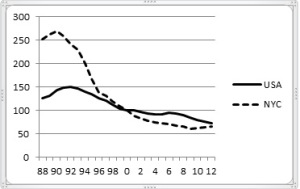

I am in the process of writing a book about crime in New York City that will cover the last twenty-five years and will be based, in part, on precinct-level crime data that covers the entire period, much generously supplied to me by several scholars who have published in this field. The chart below shows the annual rate of violent crime (2000 as base year) in the USA and New York City from 1988 through 2012:

This comparison creates a bit of a problem for Mayor Bloomberg’s crime-fighting image, never mind his legacy. First, while violent crime fell dramatically over the twenty-four years captured by the data, the most significant decrease occurred prior to 2002, in other words, before Mayor Mike arrived at City Hall. Second, the decline in violent crime during Bloomberg’s tenure took place during his first two terms, whereas the violent crime rate actually increased in his last term, while the national violent crime rate, which rose slightly between 2003 and 2008, now continues to fall.

New York City’s increase in violent crime since 2008 has been masked by two factors: (1). A very significant decline in homicides, which have now dropped to an annual rate not seen since the end of the Korean War; and (2). a possible overcount in the city’s estimated population in the years leading up to the 2010 census, which would depress crime rates, even if raw numbers remain unchanged. Finally, citywide crime data or even data aggregated at the borough level can’t really explain how crime affects the average city resident, because each neighborhood is almost a city within itself, and each has very different profiles when it comes to crime. For example, Brooklyn Heights is a lovely, toney and wealthy neighborhood with great views of the Upper New York harbor and a crime rate as low as you can get. In 2013 there was 1 homicide in Brooklyn Heights, which works out to an annual murder rate of less than 2. Walk one mile east into Fort Greene and the murder rate per 100,000 last year was 12. Stroll another mile east to Brownsville (below) and you’re on streets where the murder rate was 16.

Criminologists have been debating the reasons why violent crime continues to decrease both nationally and within New York City, but nobody’s come up with a definitive answer as of yet. One scholar, Frank Zimring, has published a very good book on New York City crime, entitled The City That Became Safe. But his data only goes through 2007, and while he argues that the city became safer because of stop-and-frisk, the NYPD continued that strategy through at least 2011 and crime rates went back up.

Violent crime is a multi-faceted behavioral phenomenon whose causes lie very deep within the social fabric of the community, and I’m not sure we really understand enough about high-crime communities to know why it occurs. The good news is that while Compstat may not yet be able to eliminate crime, it certainly can tell us where and when crimes occur. All we have to do is figure out the why.

Recent Comments